Customer Services

Customer Support

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Full description not available

V**D

National Socialism doesnt work.

The idea is presented that Nazi Germany died not because of the military losses, but lost militarily because the people could no longer stomach the lies of their leaders. The image presented is the ease with which left wing socialist politics slides into right wing national socialism. This happens in every nation. The more passionate is the left, the more brutal is the application of the apparently left wing policies.

D**G

Comprehensive, insightful, and relevant

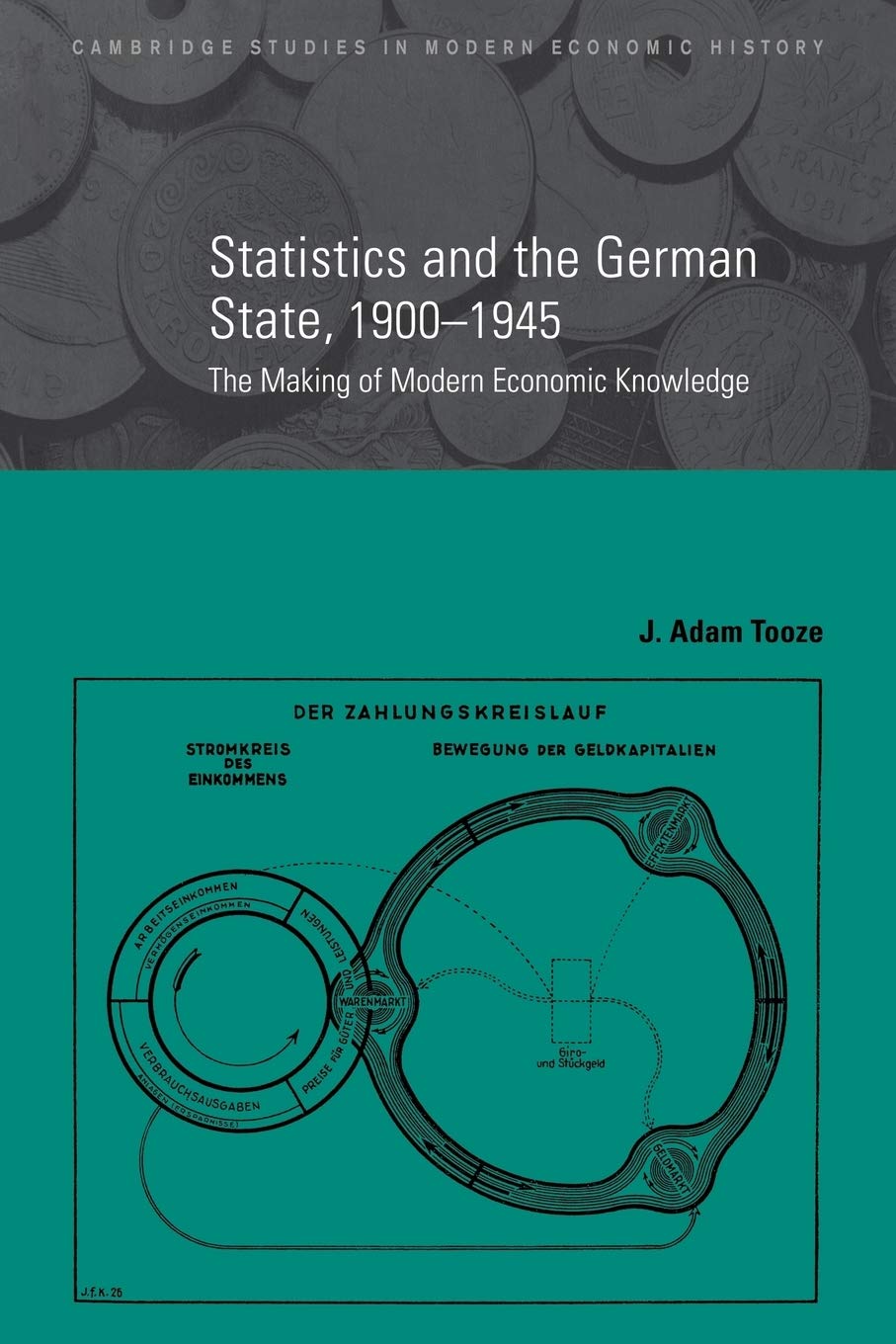

The author describes the explosive development of statistical theory from the 1870s through WWII in Germany, and to a lesser extent worldwide. He discusses the revolution of statistics and its complex interwoven relationship with different political regimes.The adoption and application of improved statistical methods coincided, not unexpectedly, with technological improvements in data-processing. Statistics can now be seen as complementary infrastructure for the field of macroeconomics. It began to define the way economics was comprehended. Unemployment “increases” as opposed to “spreads”. Statistics also made growth of modern States possible. Not only could statistics be used in an attempt to evaluate policy, but to identify opportunities for policy intervention.Interwar Germany saw a large outgrowth of statistical usage by State departments, providing statisticians significant power. This lack of division between statistics and policy was unprecedented. As a result statistical measurement expanded to every aspect of life and reduced masses to numerical categorization. This quantification of individuals, in conjunction with Nazi ideology, facilitated the violent genocide that took place.Despite later Nazi goals of racial cleansing, German economic policy, at least at first, was reminiscent of modern social and industrial policy. At the turn of the 20th century, industrial concentration in capitalist Germany, hidden by the structure of Wilhelmine era statistics, was expected to result in a Marxist revolution of the proletariat. Instead, consistent with Gustav Schmoller’s analysis, a skilled middle class emerged, supportive of private industry. While larger firms were putting small firms out of business, medium-sized businesses were emerging and prospering as well. Socialist ideals remained popular, but the party had to work hard to misconstrue increasingly popular statistical data indicating improvements in living standards. Nonetheless a gap existed between Wilhelmine era statistics and theory. Statistics lacked concept, while academics lacked empirical rigor.German firms were far more suspicious of State statistical office questionnaires than their counterparts in the USA and UK, limiting the information available to Germany in the pre-war period. Questionnaires had to be contoured in an acceptable way for firms to cooperate, resulting in potentially misleading data.From the creation of the German state in 1871 on, there was very little national economic policy. The Reich was restricted to trade policy. An independent economic department didn’t exist until WWI. As a result, most Wilhelmine era issues were social.Anti-administration became a popular political stance in Germany during WWI, resulting in more restrictions and a smaller budget for official statistical collection. This made war-time rationing and production management difficult, and sparked a complete turnaround, wherein the State decreed mandatory information reporting under harsh penalties for disobedience with hopes of improving centralized resource allocation. Still, official statistics were largely absent for most of war-time management. Some wanted to expand war-time management beyond the war (State socialism), but vested industrial interests and bad mismanagement of food production during WWI prevented this from occurring.The Wilhelmine era ultimately collapsed with WWI. Small firms proved expendable while large corporate firms were crucial for centralized production, contradicting anti-capitalist mantras to that point. Corporate Germany proved more resilient than the unified German State itself, which was unstable following the war.State institutions rose and fell in the mid-war period, but the eventual political stabilization during this period included heavy focus on economic planning and statistical measurement to deal with post-war recovery, reparations, hyperinflation (1924ish), and the Ruhr crisis. Hyperinflation created its own challenge, as collected statistics became increasingly stale. The mid-war approach to statistics focused on reconfiguring data collection methods for an economy with larger capitalist firms consisting of numerous legal entities, rather than small artisanal shops.The German mid-war, post-hyperinflation policy was termed “capitalist protectionism”, a technocracy of public-private cooperation. Government regulation and central organization became widespread, with at least 50% of prices set by government or government-supported private cartels. Public expenditure increased significantly, though the German statistics office was still supported financially by private business nearly as much as public funds (labor unions were a small contributor as well).The statistical office emphasized aggregate national accounting identities to plug into macroeconomic circular flow models. This led to the realization that production had collapsed during the hyperinflation. The concept of balance of payments also evolved here by matching capital and current account movements.German mid-war post-hyperinflation policy goals were strictly Keynesian. Private spending shortfalls were to be countered by expanded public spending. Monetary policy was considered inadequate, since private investment is driven by profit expectations, not cost of funds. Crowding out was considered immaterial. However, these policies never really materialized. Led by Harvard, empirical business cycle research took off globally in the 1920s (growth deconstruction into trend, seasonal, and actual business cycle), losing favor after failure to predict the Great Depression in favor of the Keynesian revolution.The relationship between the statistical office and German government was strong in the late ‘20s, with mass publication of indicators and trends. When the depression hit, significant conflict arose between the statistical office and political establishments. Government pursued a deflationary policy to become more competitive internationally and reduce the cost of living (and return to the pre-war gold/currency parity), but continued to subsidize and protect agriculture. Thus food prices did not fall, while wages did. Government blamed the statisticians for the weight they gave to foodstuffs. The statistical office also frequently contradicted government budget projections with far more pessimistic projections. National Socialists (like Hitler) harped on the published economic statistics, depicting high unemployment and high cost of living. His primary narrative was ending reparation payments.The statistical office’s economic predictions during the Great Depression were relatively optimistic. They saw a recession, but thought it would be domestic and confined to industry. The lack of foreign demand for commodities hurt German agriculture, resulting in the turn to protectionism, hurting domestic consumers and German exports. Global credit markets collapsed, so the turn to deflationary policy was not exactly the first option. German private banks were required to hold gold and foreign reserves to back notes in circulation (at 40%), but no reserve requirements were in place for non-paper fiduciary media issued, allowing short-term liabilities to fund long-term assets without limit. So when foreign depositors began to withdraw, Germany turned to exchange controls and suspended payments on obligations This helped stop bank failures, but lending still dried up.Britain then left the gold standard by devaluing their currency. A floating exchange rate regime casted doubt on deflationary policy. This hopeless situation resulted in radical polarization of German political parties. Following clashes with politicians and cut funding, the statistical office became a Nazi hotbed, characterized by “youthful” pro-intervention economic nationalism.Germany ended up leaving the gold standard in ’31. Hitler came to power in ’33. Under Hitler, statistical offices expanded dramatically with the aim of imposing state control on an increasingly militarized economy. Trade deficits resulted in dwindling foreign exchange balances, threatening rearmament, and providing justification for more comprehensive state control of business (to reduce foreign vendors). The official statistics office became larger and more comprehensive than ever. Industry interrelations were tracked similar to Leontief’s input-output analysis (itself an improvement on Quesnay’s table). Depicting the economy as a matrix, one can specify desired outputs and invert the matrix to find the associated inputs to achieve that output bundle. Alternatively, one can do each input stage separately, iterating until increments become tiny, approximating the inversion solution. The goal was central planning, but information demands from different government departments became insurmountable, as businesses small and large incurred unrelenting bureaucratic data requests, creating new animosity between business and the statistical office. As controls were put in place to manage information requests, conflicting motivations (like catching tax evaders) muddled the control setting process and threatened the confidentiality/anonymity of individuals and businesses.Nazi extremism resulted in the collapse of the statistical office, and the input-output approach to planning, in the mid- to late-1930’s, as confidential statistical data was being used for authoritative surveillance, and military buildup / national independence overtook economic planning in importance. Liberalism was considered antiquated.Military economic planning had difficulty accounting for the physical balances of the plethora of different types of manufactured goods. Some goods had to be measured in weight, some in units. The task of coordinating and recording these thousands of goods and processes was beyond the capabilities of the time. They instead used market prices to aggregate goods, but this relied on the existence of market prices, which was highly suspect after price freezes in 1936. After numerous other unforeseen difficulties across the production supply-chain, economic planning failed to be implemented prior to WWII.In the late 1930s, statistical analysis was revolutionized in Germany with a decentralized method of collecting statistics. The data was made available to everyone, so the financial condition of every individual and business was no longer private. However, the data itself was too raw and incomplete to have any use in planning, so it was largely an end in itself. Full transparency also led to gaming by data providers. Classification went static after WWII started, so production changes were unaccounted for during the war. By the 1940s, the official statistics office, which survived due to its private funding component, had retaken control of German statistics, with input-output analysis and centralized use of the census back on the table, but data requests to individuals soon became overbearing once again, leading to another statistical reprioritization mid-WWII.Ultimately, through the brutal exploitation of thousands of slave laborers and forced conversion of commercial businesses, the centrally planned militaristic German economy sustained military production at high levels throughout the war.Late in WWII, Germany centrally planned both civilian and military production. They soon realized that they would either have to massively overhaul all producers to meet standardized production plans, or contour plans to meet uncountable production idiosyncrasies. Bottlenecks were common, with some producers short on components, and other short on labor. There was little detail on components used to make components, so higher-order goods went largely untracked. Comprehensive consumer rationing was considered, as was mass industry standardization and elimination of all decentralized decision making. Military defeat, and German business protest, put an end to this totalitarian planning revolution in favor of a more liberal economic approach that found support in the open-minded German culture of the time.

R**N

More Interesting than It Seems

This is one of those books devoted to an apparently narrow topic that illuminates broader issues. The core of the book is a narrative of how the collection and analysis of economic statistics changed from 1900 to 1945. What makes this apparently dry topic interesting is how Tooze connects it to 2 larger issues, the nature of the German state in this period and the evolution of economic theory and policy.Its a truism that the collection of important national statistics is a consequence of the expansion of the state. One of the things that Tooze shows nicely is how the activities of German statistical bureaus reflects the nature of the state. In Wilhelmine Germany, there was a vigorous effort to collect national economic statistics but Tooze shows the significant limitations of this effort. The limitations occur in 2 broad categories. First, the federal nature of the Wilhelmine state and the ability of German business to resist certain types of data gathering limited the reach of the central statistical office. Second, much of the data gathered was predicated on an out-dated conception of the German economy as a traditonal craft-based system. The information deficiencies became particularly important during WWWI when there were efforts at national economic direction. In common with other aspects of German wartime economic management, the data collection efforts of the central bureau were increasingly chaotic and unsuccessful.In the Weimar period, the central statistical bureau was quite dynamic, pioneering new methods of data collection, new indices of economic activity, and a closer look at the German economy. Tooze emphasizes not only the relative dynamism of the Weimar state but also the way in which innovative activities of economic statistics interacted with and were driven by the emerging discipline of macroeconomics. This is his second major theme. Tooze emphasizes both the important international context with the Germans influenced by innovations in other nations and the innovations of the Germans themselves. By the end of the 20s, the collection of statistics was bound up with novel macroeconomic theories and the articulation of counter-cyclical fiscal and monetary policies. Tooze goes on to look the visscitudes of the statistical system under the Nazis, the efforts of statisticians to develop their own programs and bureaucratic fiefs in the chaotic and polyocratic world of the Nazi state and complex but ultimately futile efforts to develop the information network to manage a command economy driven by wartime needs.Tooze is very good writer and the integration of economic history, history of economic theory, and political history is excellent. While this book is most profitably read specialists, it has some general significance.

Trustpilot

1 month ago

1 day ago